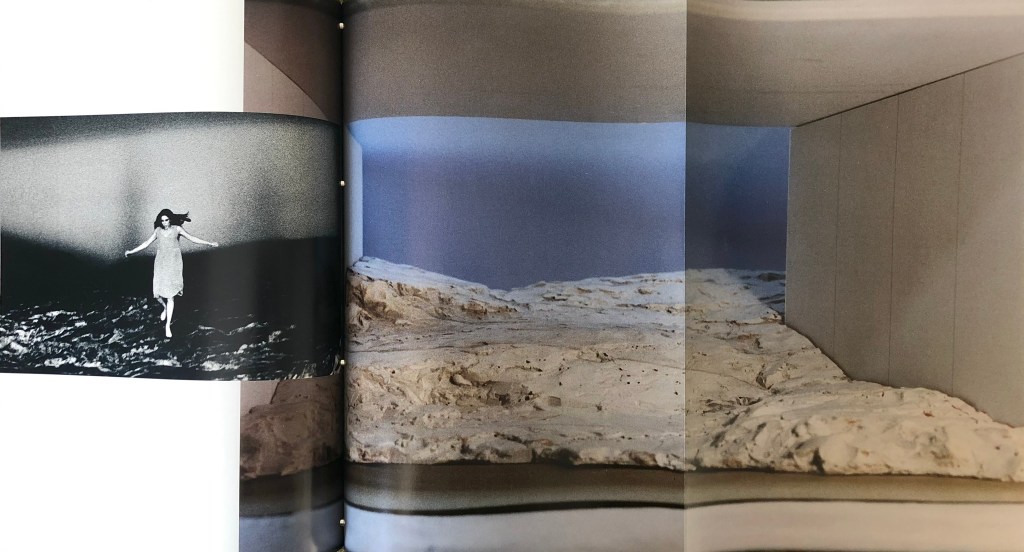

TL;DW

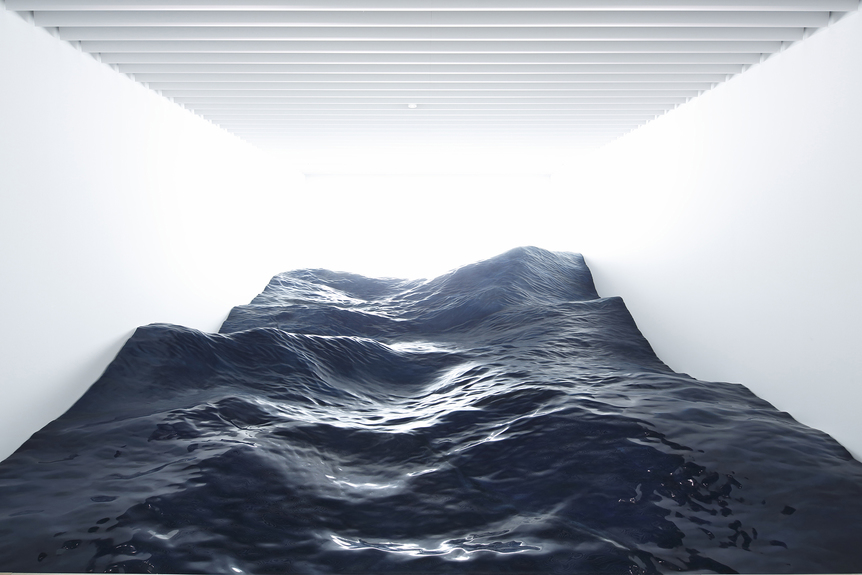

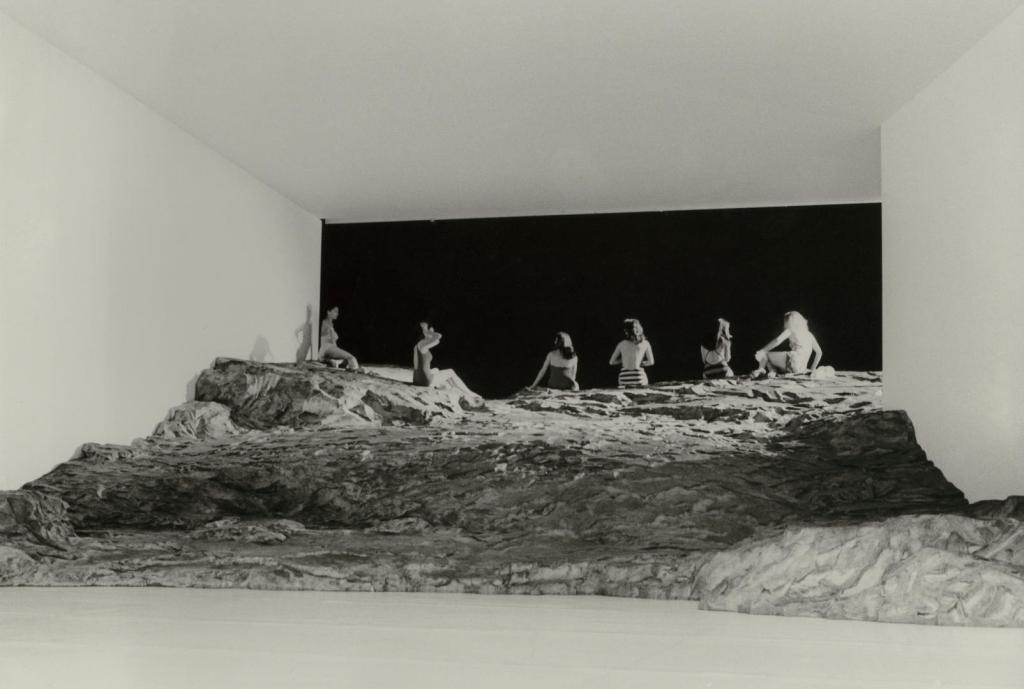

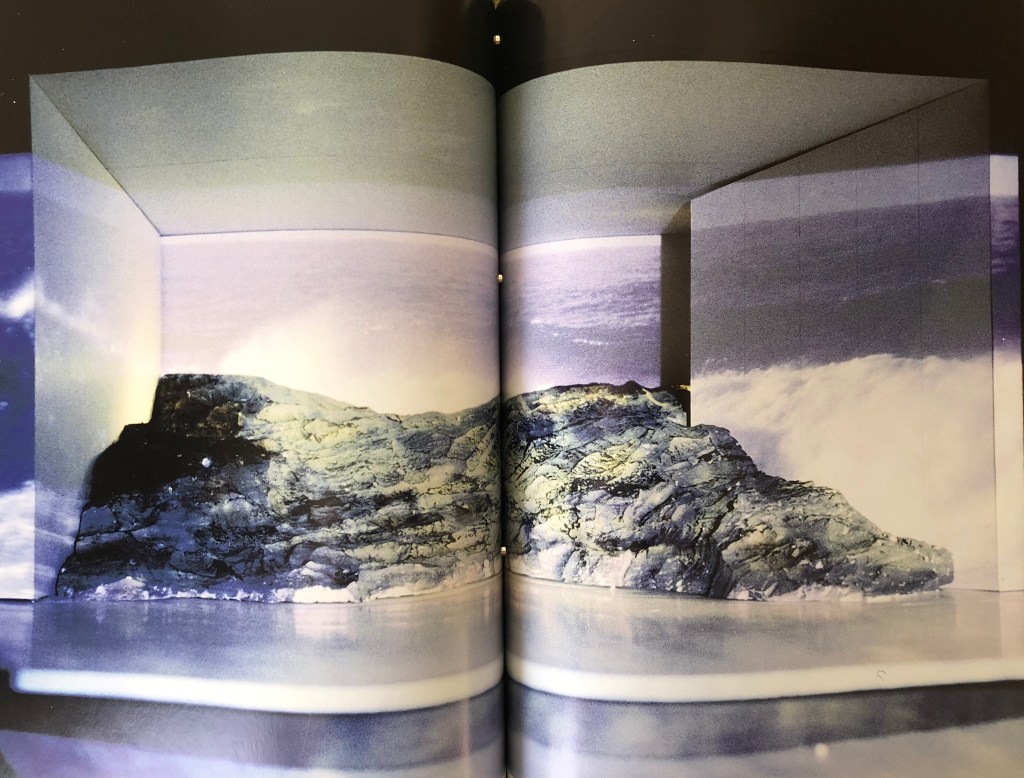

A VJ essay of demonically dancing (and singing and speaking) women

on Sunday menses

over god knows what kind of bloody shoddy fancies. xxe

TL;DW

A VJ essay of demonically dancing (and singing and speaking) women

on Sunday menses

over god knows what kind of bloody shoddy fancies. xxe

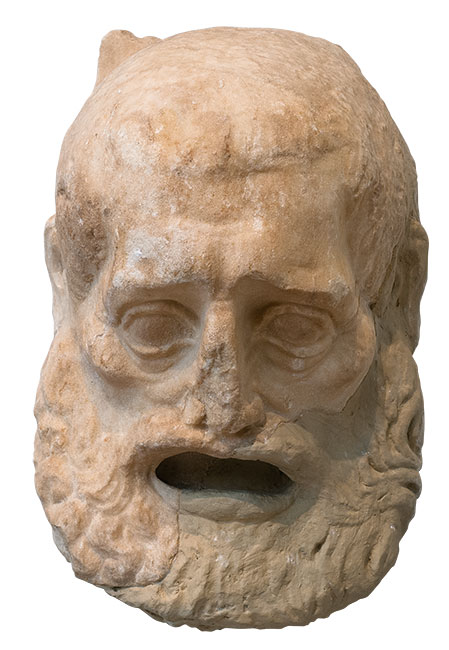

I should thank Zilan for sending me a crazy quest for archaelogical remnants or replicas of ancient tragedy and comedy masks particularly from Asia Minor, only to arrive at this vertiginous cycle of representation: A bronze applique, copied out of a statue of Attis–the castrated hermaphrodite daemon of Phrigian cult of Kybele–which demonstrates them in a pose where they are about to wear a tragic mask. I couldn’t find further information, but I guess it is likely that this is an Imperial age Roman remake of a Classical antiquity or Hellenistic original, coming down to us through German art historian Wilhelm von Bode’s acquisition in 1891. This endless movement of supplement, this turning down the spiral aspect of mimesis hooked me up to theatre and dance until I die. Not to mention the politics of sexuality and of truth inherent in this repetition after repetition after repetition. Hey Konstantina, would that count as lateral dramaturgy?

And somehow, Susanne Kennedy and Markus Selg’s Angela (a strange loop) is powered by the same force, only turned awry and nauseaus in the age of post-simulacra. Fransien van der Putt has a similar take in her extended review.

“I write words on my throat so they would vibrate” dedi kız filmde. Ben de ona bu şiiri yazdım:

Ne ateş yakmasını bilirim, ne ateş söndürmesini

Soğuk su içip hastalanmamayı

Yıldızlardan yorgan yapmayı

Evi kurmayı beceremem çamurdan

Zehirsiz dalı, sağlam taşı seçemem

Canavarlar uyanıyor yeniden, milyonlar evvelinden

Biliyorum, işgâldeyim

Ölmeyi hak ediyorum, ama bağımlıyım yaşamaya

Anlamını bilmeden.

Küçük bir kızın saf öfkesi, insanötesi adalet arayışı, intikamı [daha sonra bunu Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead‘in kocakarısında da izleyecektim]. Herkes seyrediyor. Kelimeler tene yazılıyor. Ağzıyla tek söz söylemese de aslında hiçbir şeyi öldürücü ketumlukta taşımıyor. Dik dik bakıyor, kameranın gözüyle dünyaya dağıtıyor. Herkes hak ettiğini buluyor, herkes suçunu ağzıyla itiraf ediyor.

ikisini de anavatanlarında izlemedim (sen kalk doğrudan ghent’e git bir de), peki beni webster hall studio’nun pogo’sunda dişlerimi dökmekten kurtaran kimdi, işte bunlar hayatın cevab verilemeyen gizemleri olarak kalacak.

bonus 1:

bonus 2:

This talk was given for Composers Inc., on the campus of the University of California at Berkeley in the fall of 1986. To prepare it for print I have had to truncate it and fiddle it around, since I had to omit most of the readings it was the matrix of (though I left in “She Who” as bait), and since my composer-collaborator Elinor Armer could not join me on the page as she did on stage to talk about the text/music piece we were about to premiere. But to smooth it all down into a proper essay seemed to be in bad faith towards its subject; it was a performance, and so on the page it has some of the queerness and incompleteness of all oral works written down.

The printed word is reproducible. You can type the word “sunrise” or print it in type or on a computer screen or printout, and it’s the same word reproduced. If you handwrite the word “sunrise” and then I handwrite it, I’ve reproduced it, I’ve copied it, though its identity is maybe getting a little wrinkly and weird around the edges. But if you say “sunrise” and then I say “sunrise,” yes, it’s the same word we’re saying, but we can’t speak of reproduction, only of repeating, a very different matter. It matters who said it. Speech is an event. The sunrise itself happens over and over, happens indeed continuously, by way of the Earth turning, but I don’t think it is ever legitimate to say, “It’s the same sunrise.” Events aren’t reproducible. To say that the letters O and M “make” the word “OM” is to confuse sign and event, like mistaking a wristwatch for the rotation of the planet. The word “OM” is a sound, an event; it “takes” time to say it; its saying “makes” time. The instrument of that sound is the breath, which we breathe over and over, by way of being alive. Indeed the sound can be reproduced mechanically, but then it has ceased to be, as we say, live. It’s not the event, but a shadow of it.

Writing of any kind fixes the word outside time, and silences it. The written word is a shadow. Shadows are silent. The reader breathes back life into that unmortality, and maybe noise into that silence.

People used to be aware that the written word was the visible sign of an audible sign, and they read aloud—they put their breath into it. Apparently if the Romans saw somebody sitting reading silently to themself they nudged each other and sniggered. Abelard and Aquinas moved their lips while they read, like louts with comic books. In a Chinese library you couldn’t hear yourself think, any more than you can in a Chinese opera.

So long as literacy was guarded by a male elite as their empowering privilege, most people knew text as event. What we call literature was recitation: the speaking and hearing, by live people gathered together, of a more or less fixed narrative or other formal structure, using repetition, conventional phrases, and a greater or lesser amount of improvisation. That’s the Odyssey, the Bhagavad-Gita, the Torah, the Edda, all myths, all epics, all folktales, the entire literature of North America, South America, and much of Africa before the White conquests, and still the literature of many cultures and subcultures from New Guinea to the slum streets.

Yet we call the art of language, language as an art, “writing.” I’m a writer, right? Literature literally means letters, the alphabet. The oral text, verbal art as event, as performance, has been devalued as primitive, a “lower” form, discarded, except by babies, the blind, the electorate, and people who come to hear people give lectures.

What, in fact, are we doing here—me lecturing, you listening? Something ever so ethnic. We’re indulging in orality. It isn’t illegal, but it’s pretty kinky. It’s disreputable, because oral text is held to be “inferior” to written—and written really now means printed. We value the power of print, which is its infinite reproducibility. Print is viral. (Virile is now subsumed in viral.) The model of modern Western civilization is the virus: the pure bit of information, which turns its environment into endless reproductions of itself.

But the word, she squeaks, is not information. What is the information value of the word “fuck”? Of the word “OM”?

Information is, or may be, one value or aspect of the word. There are others. Sound is one of them. Significance does not necessarily imply reference to an absent referent; the event itself may be considered significant: for example, a sunrise; a noise. A word in the first place is a noise. To the computers all aspects of the word other than information are “noise.” But we are not computers. We may not be very bright, but we are brighter than computers.

It is high time that I did what I am talking about, so here is a fragment of a story from an oral literature, written in the form in which we usually read such literature.

Then the great Grizzly Bear took notice of it. She became angry, ran out, and rushed up to the man who was scolding her. She rushed into his house, took him, and killed him. She tore his flesh to pieces and broke his bones. Then she went. Now she remembered her own people and her two children. She was very angry, and she went home.

Franz Boas wrote the story for us that way, in that form, as information—part of the information he was gathering about Tsimshian culture. But before that, in the first place, he wrote it down in Tsimshian as he heard it, as it was spoken, performed for him; and then he did an interlinear word-for-word translation into English. And that translation, arranged in breath-groups, reads like this:

Then she noticed it,

the great Grizzly Bear.

Then she came,

being sick in heart.

Then quickly she ran out at him,

greatly angry.

Then she went where the man was

who scolded.

Then into that place she stood.

Then she took the man.

Then all over she killed him.

It was dead,

the man.

All over was finished his flesh.

Then were broken all his bones.

At once she went.

She remembered her people,

where her two cubs were.

Then went the great Grizzly Bear.

Angry she was,

and sick at heart.

As Barre Toelken (from whom I took these illuminating passages) says, the literal translation is direct, dramatic, strange.* It has a pace, a rhythm, that makes you hear it even reading it in silence on the page. What Boas did with the passage was turn it into prose. As the fellow in Molière says, “You mean I’ve been talking prose all my life?”—but in fact, he hadn’t. Prose is an artifact of the technology of writing. The Tsimshian text, and Boas’s first transliteration of it, is actually not prose, nor poetry, nor drama, but the notation of a verbal performance.

Originally music was recited just as verbal text was (and we still say “recital” for a solo performance of music). It was performed from memory, by imitation and rote learning, more or less exactly repeating an original, with considerable latitude for variations, or else improvised according to strong guiding conventions of structure and technique.

Notation—the writing of music and the means of printing it and now the photoreproduction technology that makes even manuscript infinitely reproducible—had a huge effect on both the composition and the performance of music. Yet there is a lot of music that actively resists or evades notation, including some of the liveliest contemporary music (jazz, synthesizer composition). And written music, in any case, did not replace performance. We don’t go to the symphony or the rock concert and each sit there reading a printed score in silence.

But that’s exactly what we do in the library.

Why did it happen to words and not to music? A dumb question, but I need an answer to it. Which, I guess, might be that the note is purely a sound, the word impurely a sound. The word is a sound that symbolizes, has significance; though it is not pure information, it is or can function as a sign. Insofar as it is a sign it can be replaced by another sign, equally arbitrary, and this sign can be a visual one. The note, having no symbolic value in itself, no “meaning,” can’t be replaced by a sign. It can only be indicated by one.

Word spoken and note sung both enter the mind through that whorled and delicate fleshly gateway the ear. Poem written or song written come through that crystalline receiver of quanta the eye, in search of the inner, the mental ear. In music, this eye detour is a convenience, an adjunct only; music goes on being what is sounded and heard. But the written word found a detour past both outer ear and inner ear to nonsensory understanding. A kind of short circuit, a way around the body. Written text can be read as pure sign, as meaning alone. When we started doing that, the word stopped being an event.

I’m not complaining, you know. If it weren’t for writing, for books, how could I be a novelist married to a historian? Written language is the greatest single technology of the storage and dissemination of knowledge, which is the primary act of human culture. It gives us all the libraries full of books of science, reference, fact, theory, thought. It gives us newspapers, journals. It gives us interoffice memos, catalogues of obscure forms of potholder and electric tempeh shredder, and the reports of federal committees on deforestation printed on paper that used to be a forest. That’s how it is—we’re literate. And we’re word processors now too, since information theory and the computer are hooked up together. That’s dandy. But why do we lock ourselves into one mode? Why either/or? We aren’t binary. Why have we replaced oral text with written? Isn’t there room for both? Spoken text doesn’t even take storage room; it’s self-recycling and does not require wood pulp. Why have we abandoned and despised the interesting things that happen when the word behaves like music and the author is not just “a writer” but the player of the instrument of language?

The stage: yes. Plays get printed, but their life is still clearly in performance, in the actors’ breath, the audience’s response. But the drama isn’t central to our literature any more. Nor is the aesthetic power of the language of drama central to it, at present. The power and glory of Renaissance plays, or of a writer as recent as Synge, is the language; but for fifty years or more we’ve been satisfied in the theater by the mere selective imitation of common speech. I wonder if this isn’t partly the influence of movies and TV. A play is words, it is nothing but words; in film the words are secondary, the medium is a visual one where the strongest aesthetic values are not verbal at all.

That doesn’t mean that words have to be as badly treated as they are in most film and TV drama. The media use words like they were sanitary landfill. Even radio, the aural medium par excellence, where in the early decades there was a lot of real wordplay, mostly uses words only to give the news and weather. Talk shows aren’t art, and rock lyrics keep getting more rudimentary. Radio drama has made a small comeback on NPR, and NPR radio readings have led to a demand for cassettes of readings to play during commuter gridlock, but that’s still a tiny sideline to book publishing. Our text is still silent.

Where have I heard language as art? In some, some few, speeches—Martin Luther King…. In some well-told ghost stories at the campfire, and some really funny dirty jokes, and from my mother at eighty telling us her experience in the 1906 earthquake when she was nine. From comedians with a great text, like Bill Cosby’s Chickenheart, or Anna Russell’s version of the Ring, aesthetically far superior to Wagner’s. From poets reading, live or on tape, and fiction writers performing—prose pros, you might call them. But from amateurs too. People reading aloud to each other. And here’s a point I’ve been aiming at: If you can read silently you can read aloud. It takes practice, sure, but it’s like playing the guitar; you don’t have to be Doc Watson, you can get and give pleasure just pickin’. And second point: A lot of the stuff we were taught to read silently—Jane! You are moving your lips!—reads better out loud.

Reading aloud is of course the basic test of a kid’s book. If you apply it to literary works written for adults reading in the silent-perusal mode—that is, in prose—the results can be positively, or negatively, surprising. An example: The present-tense narrative so much in vogue, particularly in “minimalist” fiction, seems more casual and more immediate than the conventional narrative-past tense; but read aloud, it sounds curiously stilted and artificial; its ultimate effect of distancing the text from the reader becomes clear. Another example: Last spring after reading Persuasion to each other, my partner and I decided tentatively and unhopefully to have a bash at To the Lighthouse. When Austen wrote, people still read aloud a great deal, and she clearly heard her text and suited its cadences to the voice; but Woolf, so cerebral and subtle and … so, we found our only problem was that our reading got impeded by tears, shouts of delight, and other manifestations of intellectual exhilaration and uncontrollable emotion. I will never read Virginia Woolf silently again, if I can help it; you miss half what she was doing.

As for poetry, the Beats brought the breath of life back to it, and then Caedmon Records, with that first Dylan Thomas recording; and these days all poets tell you earnestly that they write to be heard. I’ve become a bit skeptical. I think some of them write to be printed on the pages of magazines, because their stuff goes kind of stiff, or kind of limp, performed. Other stuff that doesn’t look like much lying on the page comes to terrific life embodied in the voice. But since poets become poets by publishing in the magazines, the premium is still on the work that works silently. The poem that works better orally can be dismissed as a “performance piece,” with all the usual disparagements of oral texts: primitive, crude, repetitive, naive, etc., etc., etc. Some techniques proper to oral poetry stick out awkwardly in print (just as eye-poetry devices like a series of one-word lines or typographical trickery are useless or worse in performance). The poets who really work in both modes at once, like Ted Hughes or Carolyn Kizer, aren’t common (but tend to be looked down upon as “common” by the magazine mandarins). My impression is that at present women are more interested in voice-poetry than men. Women may turn to the living voice, the ephemeral, subversive performance, deliberately to escape the macho-mandarin control over “literature.” One of the poems that started me thinking about this is Judy Grahn’s “She Who,” in The Work of a Common Woman (St. Martin’s Press, 1978), a poem that must be read aloud, cannot be read silently: its appearance in print is like music notation—an indication of performance.

She Who

She, she SHE, she SHE, she WHO?

she – she WHO she – WHO she WHO – SHE?

She, she who? she WHO? she, WHO SHE?

who who SHE, she – who, she WHO – WHO?

she WHO – who, WHO – who, WHO – who, WHO – who…..

She. who – WHO, she WHO. She WHO – who SHE?

who she SHE, who SHE she, SHE – who WHO —

She WHO?

She SHE who, She, she SHE

she SHE, she SHE who.

SHEEE WHOOOOOO

(When I was planning this talk I found, in a book by the Tai Chi master Da Liu, a description of Taoist breathing: “the sounds hu, shi, … blowing and breathing with open mouth … evoking harmony.” Hear that, Judy?)

With stuff like that around, I began to wonder why I had to work in silence all my life, as if I were writing in a giant library with a giant librarian always going ssshhh. …

My last book, Always Coming Home, is about a nonexistent Californian people called the Kesh, who had a lively tradition of both oral and written literature, never having scrapped one in favor of the other. Many of the translations from the Kesh in the book (the Kesh language, incidentally, came into being only after most of the translations from it were made) are texts of performance pieces, notations of verse, narrative, or drama that properly exists, like music, as sound. There is a piece of a novel, which, like our novels, exists primarily in writing to be read in silence, and equally there are transcriptions of stories told aloud, from the improvised to the fixed ritual recitation. Most Kesh poetry was occasional—the highest form, according to Goethe—and much of it was made by what we call amateurs, people doing poetry as a common skill, the way people do sewing or cooking, as an ordinary and essential part of being alive. The quality of such poetry, sewing, and cooking of course varies enormously. We have been taught that only poetry of extremely high quality is poetry at all; that poetry is a big deal, and you have to be a pro to write it, or, in fact, to read it. This is what keeps a few poets and many, many English departments alive. That’s fine, but I was after something else: the poem not as fancy pastry but as bread; the poem not as masterpiece but as life-work.

I don’t believe that such an attitude towards poetry leads, as it might seem to, to any devaluing of the poet’s singular gift, or patient craft, or sullen art. After all, Shakespeare wrote when every gent was scribbling sonnets; the common practice of an art indeed may be the surest guarantee of quality in professional practice of it.

A “secondary” professional—a critic or an English professor—might be inclined to say that the standards of nonprofessional poetry are lower. But the Kesh did not use higher and lower as values; nor do I. They used central and less central, to state where their values were, what they prized and praised; and poetry was at the center. So, not surprisingly, it is for me.

But I would certainly agree that the standards must be different. Very different. Insofar as our poetry and its criticism has been “professional,” which is to say male-dominated, I am out to subvert it wherever I can. A masculine poetics depends ultimately upon the absence of women, the objectification of Woman and Nature. If Kesh verse does nothing else, at least it spits in the eye of Papa Lacan.

After translating from the Kesh for a couple of years, I came back to English as a First Language—but changed. I had been talking womantalk, and I went on wanting to work with the voice, not the silent word. At the same time, having done a little work with technicians in sound studios, I was greatly impressed with their gifts and arts; and the two interests naturally tended to come together on tape. Audio tape of course is used principally to reproduce, to make infinite copies. But it can be used as an artistic medium in itself, working with the speaking voice, using dynamics, pitch change, doubletracking, cutting, and all the dodges and delicacies of the sound technician’s craft and the resources of increasingly refined instruments. Poets can play new games here, just as they did when printing (also a technology of reproduction) was new. Unless the poet can afford the machineries and becomes a technician, the work has to be a collaboration; but then, all performance is collaboration. Poetry as the big solo ego trip is only one version of the art; there are others, equally enjoyable and demanding.

Audio poetry is not, of course, performance: if you buy the tape you have the reproduction, not the event. You have the unmortal shadow. But at least it isn’t silent; at least the text was woven with the living voice.

* Barre Toelken and Tacheeni Scott, “Poetic Retranslation and the ‘Pretty Languages’ of Yellowman,” in Traditional Literatures of the American Indian: Texts and Interpretations, ed. Karl Kroeber (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1981). This anthology, and the work of Dell Hymes in “In Vain I Tried to Tell You”: Essays in Native American Ethnopoetics (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1981), of Dennis Tedlock in The Spoken Word and the Work of Interpretation (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1983) and Finding the Center: Narrative Poetry of the Zuñi Indians (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1978), and of others concerned with the translation of works in the great oral verbal traditions, were my only guide into the fascinating and complex subject matter of this talk when I wrote it, except for Walter J. Ong’s The Presence of the Word: Some Prolegomena for Cultural and Religious History (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1981). To enter the subject from Native American verbal art is to bypass all assumptions of the superiority or primacy of written literature, and the arrogant dismissal of performance as a secondary, unimportant aesthetic category. This saves one a great deal of time, which can be wasted in worrying over such statements as this: “Meanwhile the truth is simple and clear: ‘There are many performances of the same poem—differing among themselves in many ways. A performance is an event, but the poem itself, if there is any poem, must be some kind of enduring object’ ” (Elizabeth Fine quoting Roman Jakobson quoting Wimsatt and Beardsley). I think it is fair to say that the longer one considers that statement, the less clear, the less simple, and the less true it reveals itself to be.

After I had reworked the talk for this volume, I came upon Fine’s splendid The Folklore Text: From Performance to Print (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1984), which not only led me to Richard Bauman’s Verbal Art as Performance (Prospect Heights, Ill.: Waveland Press, 1984) and Arnold Berleant’s The Aesthetic Field (Springfield, Ill.: Charles C. Thomas, 1970), but which summarizes and synthesizes current work and theory in the whole area with genuine clarity and simplicity, though without claim to final truth. If my piece leads any readers to her book, or to the wonderful things that are happening to literary theory and practice in the realms of Native American literature both old and contemporary, it will have served a good purpose.

Ursula K. Le Guin, Dancing at the Edge of the World: Thoughts on Words, Women, Places (New York: Grove Press, 1989)

i went to bed thinking all the edits and amendments i have to do to the gargantuan text that is my dissertation. i saw getting a tattoo of ouroboros round my right arm. i woke up and saw words “occam’s razor” on my screen. life opens like a tarot spread sometimes.

You must be logged in to post a comment.